Insurance is a financial contract where you pay regular premiums to transfer specific risks to a company that pools resources from many policyholders to cover losses when they occur. Understanding how insurance works and which policies you actually need forms a critical foundation of sound personal finance and risk management.

Most people buy insurance without understanding the math behind the premiums, the logic of deductibles, or the relationship between coverage and actual financial risk. This knowledge gap costs Americans billions annually through over-insurance on low-risk items and dangerous under-insurance on high-impact risks.

This guide breaks down insurance from first principles: what it is, how it functions behind the scenes, which types matter most, and how to calculate appropriate coverage levels using data-driven methods rather than sales pitches.

Key Takeaways

- Insurance transfers financial risk from individuals to companies through pooled premium payments that cover statistical losses.

- Only insure catastrophic risks that would devastate your finances—not minor inconveniences you can afford to self-fund

- Health, auto, disability, and life insurance are essential for most people; other coverage depends on specific circumstances.

- Higher deductibles lower premiums because you retain more risk—the optimal balance depends on your emergency fund size.

- Coverage amounts should match replacement costs and income-replacement needs, not arbitrary policy limits or agent recommendations.

What Is Insurance?

Insurance represents a mathematical solution to financial uncertainty.

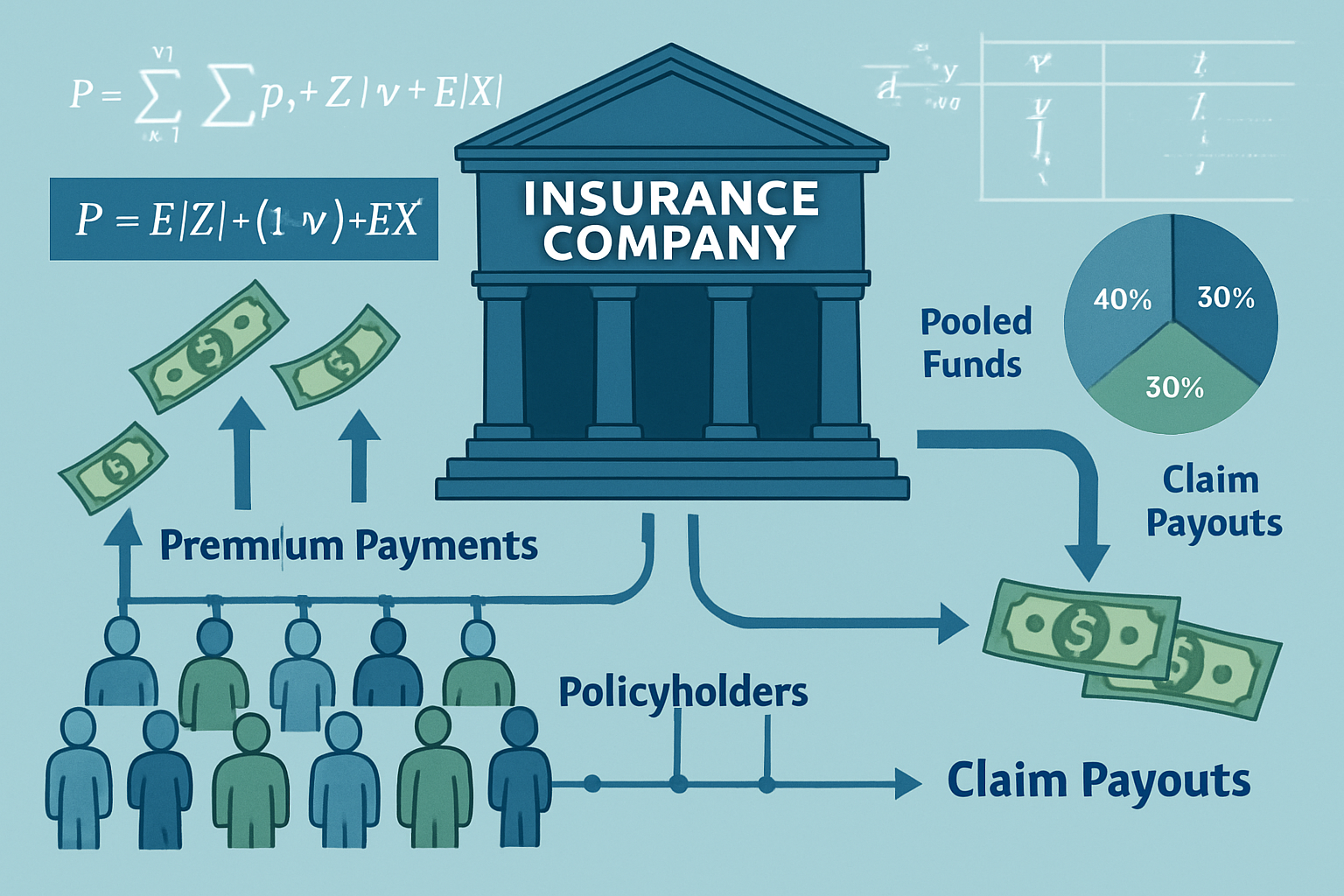

When you purchase an insurance policy, you enter a contract: you pay a known, predictable premium in exchange for protection against unknown, potentially catastrophic losses. The insurance company collects premiums from thousands or millions of policyholders, pools these funds, and uses actuarial science to predict how many claims will occur and their average costs.

The core concept is risk pooling. Not everyone will file a claim in any given year. Most policyholders pay premiums but never experience the insured loss. Those premium payments fund the claims of the unlucky few who do suffer covered losses—car accidents, house fires, medical emergencies, or premature death.

This system works because of the law of large numbers: while individual outcomes remain unpredictable, aggregate outcomes across large populations become statistically predictable. Insurance companies can accurately forecast that approximately X% of auto policyholders will file collision claims averaging $Y, allowing them to set premiums that cover expected claims plus operating costs and profit margins.

Why premiums exist: Your premium represents your share of the pooled risk plus administrative overhead. If 1,000 people each face a 1% annual chance of a $100,000 loss, the expected total claims equal $1,000,000 (1,000 × 0.01 × $100,000). Each person would pay approximately $1,000 in premiums, plus the insurer’s operational costs and profit margin.

The fundamental value proposition: you trade a small, certain loss (your premium) for protection against a large, uncertain loss (the insured risk). This trade makes economic sense only when the potential loss would significantly harm your financial position.

Takeaway: Insurance is not an investment or savings—it’s pure risk transfer. You should insure only those risks you cannot afford to absorb yourself.

How Insurance Works Behind the Scenes

Understanding the mechanics of insurance reveals why policies cost what they do and how to make smarter coverage decisions.

The Key Players

Insurers are the companies that assume risk in exchange for premium payments. They employ actuaries—mathematicians who analyze statistical data to calculate risk probabilities and set appropriate premium rates. Actuaries examine historical claims data, demographic factors, geographic patterns, and economic trends to build predictive models.

Policyholders are individuals or entities who purchase coverage. You agree to pay premiums and comply with policy terms in exchange for financial protection against specified losses.

Underwriters evaluate individual applications to assess risk levels. They determine whether to offer coverage, at what premium rate, and with which exclusions or limitations. High-risk applicants pay higher premiums or face coverage denials.

Core Insurance Components

Premiums are your regular payments (monthly, quarterly, or annually) to maintain coverage. Premium amounts reflect your risk profile, coverage limits, deductible choices, and the insurer’s cost structure.

Deductibles represent the amount you must pay out-of-pocket before insurance coverage begins. A $1,000 deductible means you pay the first $1,000 of any covered loss; the insurer pays amounts exceeding that threshold up to policy limits. Higher deductibles reduce premiums because you retain more risk.

Coverage limits define the maximum amount an insurer will pay for covered losses. A $300,000 liability limit means the insurer pays up to $300,000 for covered liability claims; you’re personally responsible for any excess.

Policy exclusions specify what the insurance does NOT cover. Standard homeowners’ policies typically exclude flood damage and earthquakes, requiring separate policies. Reading exclusions prevents unpleasant surprises when filing claims.

The Claims Process

When you experience a covered loss, you file a claim—a formal request for payment under your policy terms. The insurer assigns a claims adjuster who investigates the loss, verifies coverage, and determines the payout amount.

The adjuster reviews documentation (police reports, medical records, repair estimates, photographs), assesses whether the loss falls within policy coverage, and calculates the payment based on actual damages, policy limits, and deductible amounts.

Once approved, the insurer issues payment minus your deductible. Processing times vary from days to months, depending on claim complexity.

According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), the average auto insurance claim takes 30-45 days to settle, while complex homeowners’ claims can extend beyond 90 days[1].

Insight: The insurance business model depends on collecting more in premiums than paying out in claims and expenses. Insurers invest premium income to generate returns, creating additional revenue beyond underwriting profits. This financial structure explains why insurers carefully manage risk through underwriting and pricing.

Types of Insurance You Actually Need

Not all insurance provides equal value. Prioritize coverage that protects against financial catastrophes—events that would devastate your economic security without insurance.

Health Insurance Explained

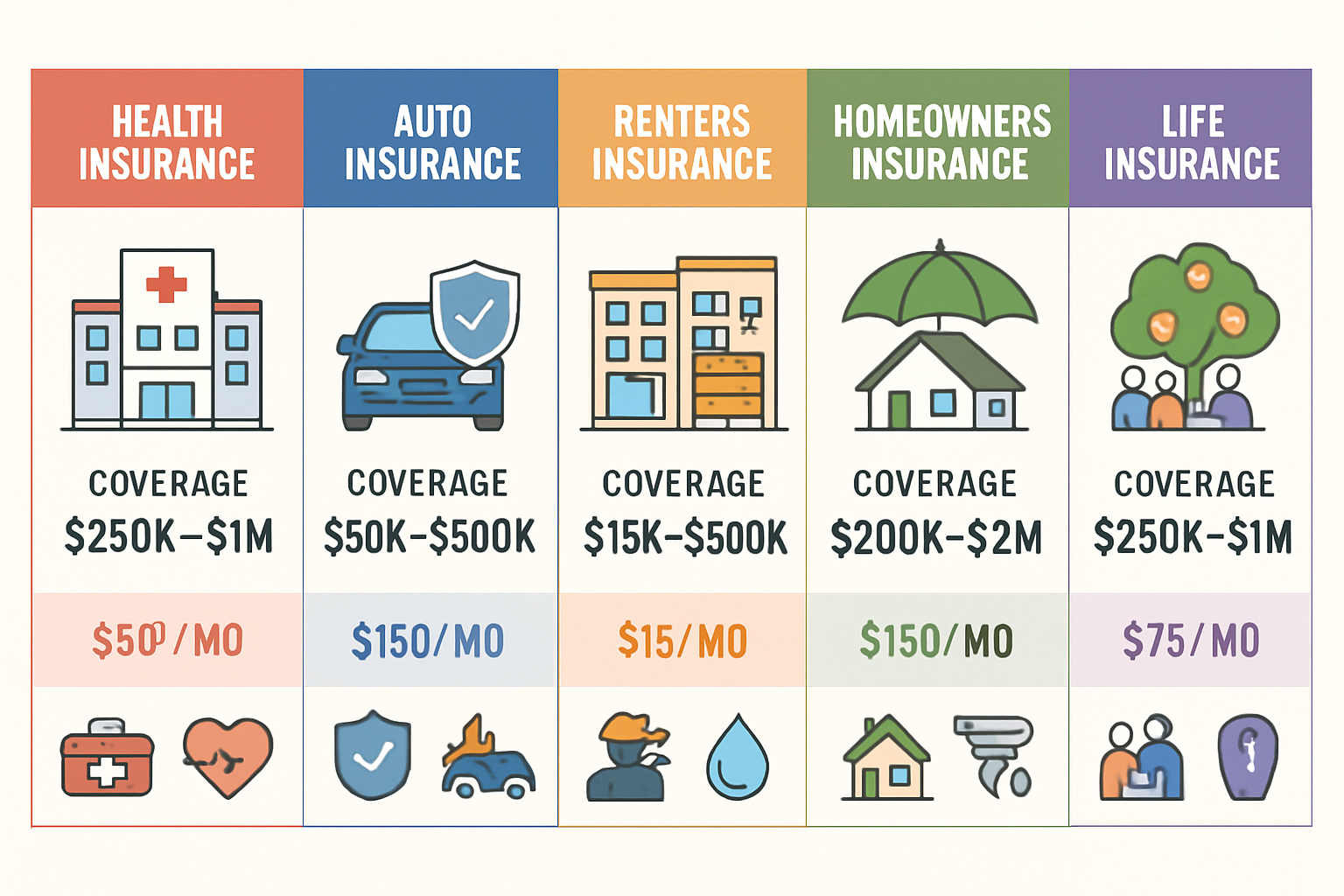

Health insurance covers medical expenses, including doctor visits, hospital stays, surgeries, prescription medications, and preventive care. Without coverage, a single serious illness or injury can generate six-figure bills that bankrupt families.

The Affordable Care Act established minimum coverage standards and prohibited insurers from denying coverage based on pre-existing conditions. Most Americans obtain health insurance through employers, government programs (Medicare, Medicaid), or individual marketplace plans.

Key components:

- Premiums: Monthly payments to maintain coverage

- Deductibles: The Amount you pay before insurance begins covering costs

- Copayments: Fixed amounts for specific services (e.g., $30 per doctor visit)

- Coinsurance: Your percentage of costs after meeting the deductible (e.g., you pay 20%, insurer pays 80%)

- Out-of-pocket maximums: Annual caps on your total spending; after reaching this limit, insurance covers 100%

Health insurance is non-negotiable. Medical debt represents the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States[2]. Even young, healthy individuals need coverage—catastrophic accidents and unexpected diagnoses occur regardless of age or lifestyle.

Auto Insurance Explained

Auto insurance provides financial protection against vehicle damage, liability for injuries or property damage you cause, and coverage for uninsured motorists. Most states legally require minimum liability coverage.

Essential coverage types:

- Liability coverage: Pays for injuries and property damage you cause to others (required in most states)

- Collision coverage: Pays for damage to your vehicle from accidents

- Comprehensive coverage: Pays for non-collision damage (theft, vandalism, weather, animals)

- Uninsured/underinsured motorist coverage: Protects you when at-fault drivers lack adequate insurance

The 20/4/10 rule provides guidance for affordable car purchases: 20% down payment, financing for no more than 4 years, and total transportation costs (payment, insurance, fuel, maintenance) under 10% of gross income.

Coverage decision: Maintain liability limits well above state minimums—$100,000/$300,000 or higher. If your vehicle’s value exceeds $3,000-$5,000, collision and comprehensive coverage make economic sense. For older, low-value vehicles, consider dropping these coverages and self-insuring minor damage.

Renters Insurance Explained

Renters insurance protects your personal belongings and provides liability coverage when you rent rather than own your residence. Landlord insurance covers the building structure but not your possessions.

Standard renters policies cover:

- Personal property: Furniture, electronics, clothing, and other belongings against theft, fire, and covered perils

- Liability protection: Legal and medical costs if someone is injured in your rental unit

- Additional living expenses: Hotel and meal costs if your rental becomes uninhabitable due to covered damage

Renters insurance costs average $15-$30 monthly for $30,000-$50,000 in personal property coverage with $100,000 liability protection[3]. This represents exceptional value—the premium equals roughly one dinner out monthly.

Why it matters: Most renters significantly underestimate the replacement value of their possessions. A basic apartment containing furniture, electronics, kitchen items, clothing, and personal items easily totals $20,000-$40,000. Replacing everything after a fire or theft without insurance creates severe financial hardship.

Homeowners Insurance Explained

Homeowners insurance protects your dwelling, personal property, and provides liability coverage for property owners. Mortgage lenders require coverage as a loan condition.

Standard coverage includes:

- Dwelling coverage: Rebuilds or repairs your home’s structure after covered damage

- Personal property coverage: Replaces belongings damaged or stolen

- Liability coverage: Protects against lawsuits for injuries or property damage you cause

- Additional living expenses: Covers temporary housing during repairs

- Other structures: Covers detached garages, sheds, fences

Critical consideration: Insure for replacement cost, not market value. Your home’s market price includes land value (which doesn’t need insurance—you can’t lose the land in a fire). Replacement cost reflects the actual expense to rebuild your home at current construction prices.

Review coverage annually. Construction cost inflation means yesterday’s adequate coverage may fall short today. Underinsurance creates devastating gaps when major losses occur.

homeowners insurance explained

Life Insurance Explained

Life insurance pays a death benefit to designated beneficiaries when the insured person dies. This coverage protects dependents from financial catastrophe following the loss of income earners.

Who needs life insurance:

- Parents with minor children

- Spouses whose income supports family obligations

- Individuals with co-signed debts

- Business partners with buy-sell agreements

Who doesn’t need life insurance:

- Single individuals without dependents

- Retirees with adequate savings and no income-dependent survivors

- Children (except small policies covering funeral costs)

The fundamental question: Would your death create financial hardship for others? If yes, you need life insurance. If no, you don’t.

Coverage amount: A common guideline suggests 10-15 times annual income, but precise needs depend on:

- Outstanding debts (mortgage, student loans)

- Income replacement duration (until children reach adulthood, spouse retires)

- Education funding goals

- Final expenses (funeral, estate settlement)

Life insurance serves one purpose: replacing lost income and covering obligations when someone who provides financial support dies. It’s not investment, forced savings, or estate planning for wealthy individuals with no dependents.

Term vs Whole Life Insurance

The life insurance industry generates enormous confusion around term versus whole life (permanent) insurance. Understanding the difference prevents costly mistakes.

Term Life Insurance

Term life insurance provides pure death benefit protection for a specified period (10, 20, or 30 years). If you die during the term, beneficiaries receive the death benefit. If you outlive the term, the policy expires with no payout or cash value.

Characteristics:

- Dramatically lower premiums than whole life

- No cash value or investment component

- Coverage ends when the term expires

- Ideal for temporary needs (covering dependents until retirement, paying off mortgage)

Example: A healthy 35-year-old can purchase $500,000 of 20-year term coverage for approximately $25-$40 monthly[4].

Whole Life Insurance

Whole life insurance combines death benefit protection with a cash value savings component. Premiums remain level for life, the policy never expires (assuming premium payments continue), and cash value accumulates tax-deferred.

Characteristics:

- Premiums cost 10-15 times more than equivalent term coverage

- Cash value grows slowly in early years due to high fees and commissions

- Policy loans are available against the cash value

- Marketed as “permanent protection” and “forced savings.”

Example: That same 35-year-old might pay $400-$600 monthly for $500,000 whole life coverage[5].

The Math Behind the Decision

The term versus whole life debate centers on opportunity cost. Whole life insurance combines two separate financial needs—death benefit protection and savings—into one expensive, inflexible product.

The alternative approach:

- Purchase term life insurance for 10-15% of the whole life premium cost

- Invest the premium difference in tax-advantaged retirement accounts

- Build wealth through compound growth in diversified investments

Numerical example:

- Whole life premium: $500/month

- Term life premium: $35/month

- Monthly difference: $465

Investing $465 monthly at 8% average annual returns generates approximately $280,000 in 20 years and $700,000 in 30 years. The whole life policy’s cash value after 20-30 years typically totals $100,000-$200,000 due to high fees, commissions, and conservative investment returns.

When whole life makes sense: High-net-worth individuals facing estate tax liability may use permanent insurance for estate planning. Business owners might employ it for succession planning. For 95%+ of people, term insurance plus disciplined investing delivers superior outcomes.

Takeaway: Buy term life insurance for protection needs. Invest the difference in low-cost index funds or high-yield savings accounts for wealth building. Don’t combine protection and investment in expensive whole life policies.

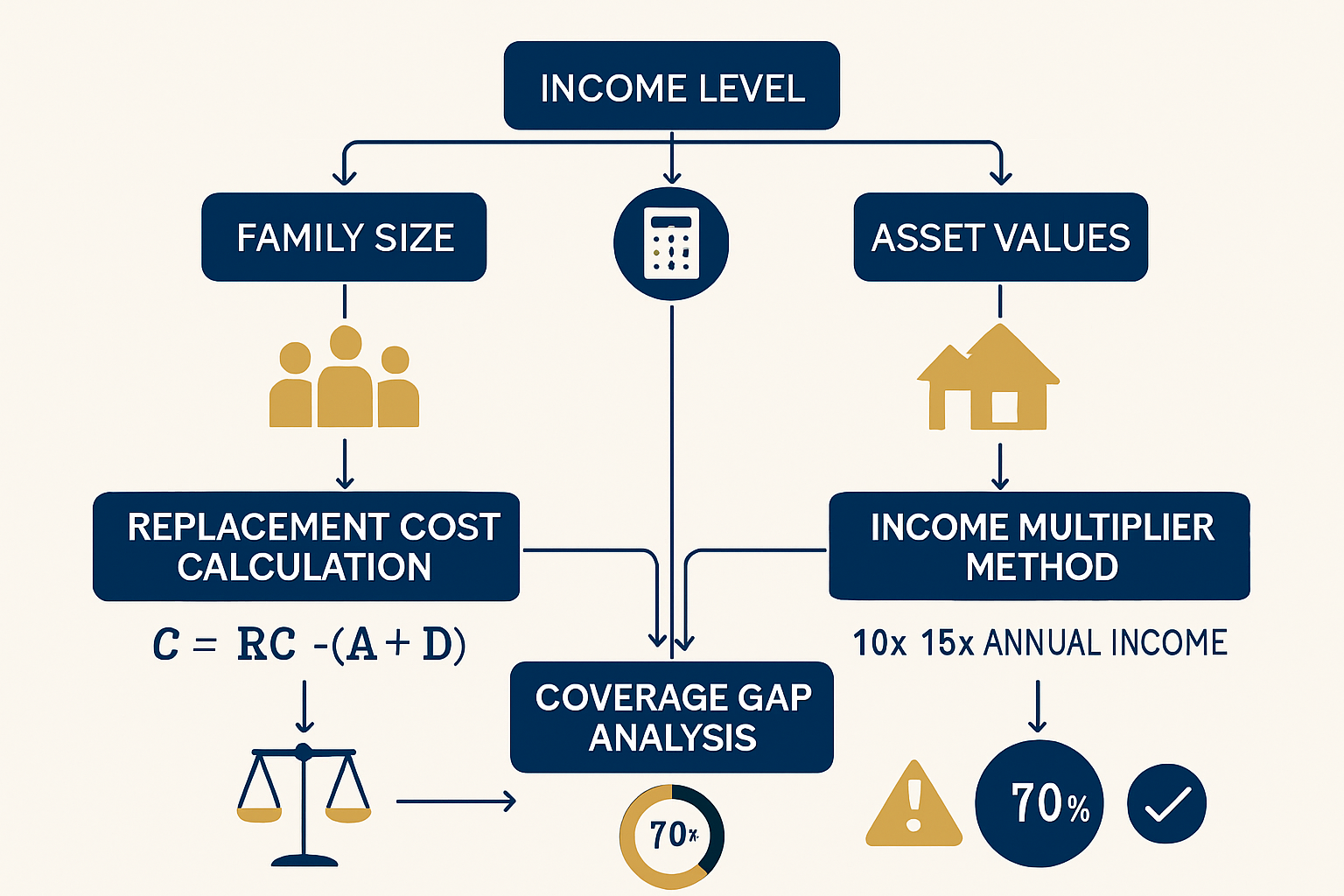

How Much Insurance Coverage Do You Need?

Determining appropriate coverage amounts requires analyzing your specific financial situation, not accepting agent recommendations or arbitrary policy limits.

Replacement Cost Logic

For property insurance (home, auto, belongings), coverage should equal full replacement cost—the amount required to rebuild, repair, or replace the insured item at current prices.

Homeowners insurance: Calculate replacement cost by:

- Determining your home’s square footage

- Multiplying by local construction costs per square foot ($100-$300+, depending on location and quality)

- Adding costs for special features (custom finishes, high-end appliances)

- Reviewing annually for construction cost inflation

Auto insurance: For newer vehicles, maintain collision and comprehensive coverage equal to the vehicle’s actual cash value. For vehicles worth less than $3,000-$5,000, consider dropping these coverages—the premium cost over several years approaches the vehicle’s value, making self-insurance more economical.

Personal property: Conduct a home inventory (photos, videos, receipts) to estimate the total value. Most people underestimate this amount significantly. A furnished two-bedroom apartment typically contains $25,000-$50,000 in replaceable items.

Income-Based Coverage Estimates

Life and disability insurance coverage should replace lost income and cover financial obligations.

Life insurance calculation:

- Annual income replacement: Multiply annual income by years of replacement needed (e.g., $75,000 × 20 years = $1,500,000)

- Debt coverage: Add outstanding mortgage, student loans, and other debts

- Future obligations: Include college funding goals, final expenses

- Subtract existing assets: Reduce coverage by savings, investments, and employer-provided insurance

Simplified formula:

Coverage = (Annual Income × 10-15) + Debts + Future Obligations – Existing Assets

Disability insurance: Replace 60-70% of gross income. If you earn $80,000 annually, target $48,000-$56,000 in annual disability benefits. Most employer policies provide inadequate coverage—review carefully and supplement with individual policies if needed.

Avoiding Over-Insurance

Insurance should protect against catastrophic losses, not cover every minor expense or inconvenience.

Common over-insurance mistakes:

- Extended warranties on electronics and appliances (high-margin profit centers for retailers)

- Low deductibles on property insurance (paying extra premium to insure small, affordable losses)

- Duplicate coverage (credit card rental car insurance overlapping with auto policy)

- Life insurance on children (emotional purchase with minimal financial justification)

- Cancer insurance, hospital indemnity, and other supplemental policies (redundant with comprehensive health insurance)

The self-insurance principle: If you can afford to replace or repair something without financial hardship, don’t insure it. Build an emergency fund covering 3-6 months of expenses, then self-insure minor risks and purchase coverage only for major catastrophes.

Insight: Every dollar spent on insurance premiums represents money unavailable for wealth building. Optimize coverage by insuring only catastrophic risks, maintaining appropriate deductibles, and self-funding minor losses through emergency savings.

Insurance Deductibles, Premiums, and Limits Explained

Understanding the relationship between deductibles, premiums, and coverage limits enables strategic policy design that balances cost and protection.

The Deductible-Premium Tradeoff

Deductibles represent risk retention—the portion of losses you agree to pay before insurance coverage begins. Higher deductibles reduce premiums because you assume more risk, decreasing the insurer’s expected payout.

Mathematical relationship:

- Increasing auto insurance deductibles from $250 to $1,000 typically reduces premiums by 15-30%

- Raising homeowners’ deductibles from $500 to $2,500 can lower premiums by 20-40%

Optimal deductible selection:

- Review your emergency fund balance

- Choose the highest deductible you can comfortably pay from savings

- Calculate premium savings over 3-5 years

- Compare savings to deductible increase

Example: Raising your auto insurance deductible from $500 to $1,000 saves $200 annually. The additional $500 deductible risk equals 2.5 years of premium savings ($500 ÷ $200). If you file a claim within 2.5 years, you break even. If you go longer without claims (likely for safe drivers), you profit from the lower premiums.

Strategy: Maintain deductibles equal to 1-2% of your emergency fund. A $10,000 emergency fund supports $1,000-$2,000 deductibles across policies.

Coverage Limits and Asset Protection

Coverage limits define maximum insurer payouts. Inadequate limits expose personal assets to liability claims exceeding policy coverage.

Liability coverage considerations:

- Auto liability: Minimum state requirements ($25,000-$50,000) provide dangerously inadequate protection

- Recommended auto liability: $100,000/$300,000 or higher

- Homeowners liability: $300,000-$500,000 minimum

- Umbrella liability: $1-$2 million for additional protection beyond underlying policies

Why higher limits matter: A serious auto accident causing permanent injuries can generate $500,000-$1,000,000+ in medical expenses, lost wages, and pain and suffering damages. If your liability coverage maxes out at $50,000, you’re personally liable for the remainder—exposing your savings, home equity, and future earnings to lawsuits and judgments.

Cost-benefit analysis: Increasing liability limits from minimum requirements to $250,000/$500,000 typically adds only $100-$200 annually to premiums. This modest cost provides enormous additional protection.

Out-of-Pocket Maximums

Out-of-pocket maximums (primarily in health insurance) cap your annual spending on deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. After reaching this limit, insurance covers 100% of additional covered expenses.

2025 ACA marketplace limits:

- Individual maximum: $9,450

- Family maximum: $18,900

Strategic consideration: High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) pair with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), offering triple tax advantages:

- Tax-deductible contributions

- Tax-free growth

- Tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses

For healthy individuals with emergency funds, HDHPs with $3,000-$5,000 deductibles and lower premiums often prove more economical than low-deductible plans. The premium savings can fund HSA contributions, building tax-advantaged medical savings.

Takeaway: Optimize the deductible-premium-limit combination based on your financial capacity. Higher deductibles and adequate limits provide better value than low deductibles with insufficient coverage.

Common Insurance Mistakes That Cost People Money

Avoiding these frequent errors saves thousands while maintaining appropriate protection.

Mistake 1: Over-Insuring Low-Risk Assets

The error: Purchasing comprehensive coverage on items you can afford to replace or that have minimal value.

Examples:

- Collision and comprehensive coverage on vehicles worth less than $3,000

- Extended warranties on appliances and electronics

- Phone insurance plans charging $10-$15 monthly with $200 deductibles

The math: A $12 monthly phone insurance premium costs $288 over two years. The deductible adds $200. Total cost: $488 to replace a phone you could purchase outright for $400-$600. You’re paying nearly the replacement cost for partial coverage.

Solution: Self-insure low-value items. Build emergency savings to cover minor losses and replacements without insurance.

Mistake 2: Under-Insuring High-Impact Risks

The error: Maintaining inadequate coverage on catastrophic risks to save modest premium amounts.

Examples:

- Minimum state liability limits on auto insurance

- Insufficient dwelling coverage on homeowners’ insurance

- No disability insurance despite depending entirely on employment income

- Inadequate life insurance for primary earners with dependents

The consequence: A single serious accident, lawsuit, disability, or death creates financial devastation that far exceeds the premium savings from inadequate coverage.

Solution: Prioritize high-limit coverage on catastrophic risks. The incremental premium cost for substantially higher liability limits remains modest compared to the protection gained.

Mistake 3: Ignoring Policy Exclusions

The error: Assumed insurance covers all losses without reading policy exclusions and limitations.

Common exclusions:

- Flood and earthquake damage on standard homeowners policies

- Business use of personal vehicles on auto policies

- High-value items (jewelry, art, collectibles) exceeding sublimits on homeowners policies

- Pre-existing conditions on some health and disability policies

Real-world impact: Homeowners in flood-prone areas discover too late that their standard policy excludes flood damage, requiring separate National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) coverage. Jewelry owners learn their $10,000 engagement ring exceeds the $2,500 jewelry sublimit on standard policies.

Solution: Read your policy declarations and exclusions. Ask agents specific questions about coverage gaps. Purchase riders or separate policies for excluded risks that matter to your situation.

Mistake 4: Never Reviewing Coverage

The error: Setting up insurance policies and never revisiting coverage as circumstances change.

Why it matters:

- Income increases require higher life and disability coverage

- Home renovations increase replacement costs

- Marriage, children, and major purchases create new protection needs

- Job changes may eliminate employer-provided coverage

- Inflation erodes the real value of fixed coverage amounts

Solution: Review all insurance policies annually. Major life events (marriage, home purchase, children, divorce, retirement) trigger immediate coverage reviews. Adjust limits, beneficiaries, and coverage types to match current circumstances.

Insight: Insurance mistakes typically involve either over-protecting minor risks (wasting premium dollars) or under-protecting major risks (exposing yourself to financial catastrophe). The optimal strategy ensures only catastrophic losses at adequate limits with appropriate deductibles.

Insurance Tools and Resources That Help

Making informed insurance decisions requires reliable information and analytical tools.

Coverage Calculators and Estimators

Life insurance calculators help determine appropriate death benefit amounts based on income replacement needs, debts, and future obligations. Most major insurers and financial websites offer free calculators.

Replacement cost estimators for homeowners’ insurance calculate rebuilding costs based on square footage, construction quality, and local building costs. These tools prevent dangerous underinsurance.

Premium comparison tools allow you to obtain quotes from multiple insurers simultaneously, ensuring competitive pricing. Independent insurance marketplaces and state insurance department websites provide comparison resources.

Educational Resources

State insurance departments offer consumer guides, complaint databases, and financial strength ratings for insurers operating in your state. These free resources help identify reputable companies and understand your rights.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) provides consumer insurance information, complaint ratios, and educational materials at naic.org.

Insurance Information Institute offers objective insurance education covering all major coverage types at iii.org.

Decision Framework

When evaluating insurance needs, apply this systematic approach:

- Identify risks: List potential losses that would significantly harm your financial position

- Quantify impact: Estimate the financial cost of each risk

- Assess probability: Consider likelihood (though this is often difficult for individuals)

- Evaluate alternatives: Compare insurance cost to self-insurance or risk avoidance

- Optimize coverage: Select appropriate limits, deductibles, and policy types

- Review regularly: Reassess annually and after major life changes

Integration with financial planning: Insurance represents just one component of comprehensive financial management. Coordinate coverage decisions with budgeting strategies, emergency fund targets, and long-term wealth-building plans.

How Insurance Fits Into Your Bigger Financial Plan

Insurance serves a specific, limited role in comprehensive financial planning: protecting against catastrophic losses that would derail wealth building and financial security.

Insurance as the Protection Layer

Financial planning hierarchy:

- Foundation: Emergency fund (3-6 months’ expenses)

- Protection: Insurance against catastrophic risks

- Debt management: Eliminate high-interest debt

- Wealth building: Retirement savings, taxable investments

- Optimization: Tax strategies, estate planning

Insurance occupies the protection layer—it prevents financial catastrophes from destroying the foundation and wealth you’re building. Without adequate insurance, a single medical emergency, lawsuit, disability, or death can eliminate years of disciplined saving and investing.

Relationship to Savings and Investing

Insurance and savings serve complementary but distinct purposes:

Insurance: Transfers catastrophic risk to companies through premium payments. Protects against low-probability, high-impact events. Provides no return on premiums paid (except peace of mind and protection).

Savings and investing: Builds wealth through compound growth. Provides self-insurance capacity for minor losses. Creates financial independence and security.

The connection: Adequate emergency savings enable higher insurance deductibles, reducing premium costs. Those premium savings can then be invested, accelerating wealth accumulation. As wealth grows, you can self-insure more risks, further reducing insurance needs and costs.

Example progression:

- Early career: Minimal assets, high insurance needs (health, auto, life if dependents, disability)

- Mid-career: Growing assets enable higher deductibles, reducing premiums; life insurance remains critical if supporting a family

- Late career/retirement: Substantial assets allow self-insurance of many risks; life insurance needs decline as dependents become independent; focus shifts to health and long-term care coverage

Risk Management First, Growth Second

The sequence matters. Attempting to build wealth without adequate insurance creates fragility—one catastrophic event destroys accumulated assets and potentially creates debt.

The optimal approach:

- Establish basic emergency fund ($1,000-$2,000 for immediate crises)

- Secure essential insurance (health, auto liability, renters/homeowners, life if dependents, disability)

- Build a full emergency fund (3-6 months’ expenses)

- Optimize insurance (increase deductibles, adjust coverage, reduce premiums)

- Maximize wealth building (retirement accounts, taxable investing, real estate)

This sequence ensures protection precedes growth, preventing financial catastrophes from derailing long-term plans.

Understanding personal finance fundamentals provides the broader context for insurance decisions within comprehensive financial planning.

Takeaway: Insurance is not investment, savings, or wealth building—it’s pure protection. Maintain adequate coverage for catastrophic risks, minimize premium costs through strategic deductible selection, and redirect savings toward actual wealth-building vehicles that generate returns.

Related Guides

Understanding insurance connects to broader financial concepts and strategies:

- Understanding risk management in personal finance

- Building emergency funds for self-insurance capacity

- Optimizing protection strategies across your financial plan

- Managing financial obligations to reduce insurance needs

💼 Insurance Coverage Calculator

Calculate how much life insurance coverage you actually need

💡 Recommendation

Conclusion

Insurance represents a fundamental risk management tool—not an investment, not forced savings, but pure financial protection against catastrophic losses you cannot afford to absorb.

The math behind insurance is simple: you trade small, known costs (premiums) for protection against large, uncertain losses (catastrophic events). This trade makes economic sense only when the potential loss would significantly damage your financial position.

The essential framework:

- Insure catastrophic risks (health crises, major liability, disability, premature death if others depend on your income)

- Self-insure minor losses through emergency savings

- Optimize deductibles based on your financial capacity

- Maintain coverage limits that protect your assets

- Review policies annually and after major life changes

Immediate action steps:

- Review current insurance policies and identify coverage gaps or redundancies

- Calculate appropriate coverage amounts based on replacement costs and income needs

- Increase deductibles to levels your emergency fund can support

- Eliminate unnecessary coverage on low-value items

- Ensure adequate liability limits on auto and homeowners policies

- Verify life and disability coverage matches current income and obligations

Insurance should consume 10-15% of your budget across all policies. If you’re spending significantly more, you’re likely over-insured on minor risks. If you’re spending significantly less, you may have dangerous coverage gaps.

The goal is not maximum insurance—it’s optimal insurance that protects against genuine catastrophes while minimizing costs and maximizing resources available for wealth building.

Understanding how insurance works, which coverage you actually need, and how to structure policies efficiently creates a solid protection foundation that supports long-term financial success.

References

[1] National Association of Insurance Commissioners. (2024). “Auto Insurance Claims Process and Timeline.” NAIC Consumer Information. https://content.naic.org/

[2] American Journal of Public Health. (2019). “Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007-2019.” AJPH Research. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/

[3] Insurance Information Institute. (2025). “Average Cost of Renters Insurance by State.” III Facts and Statistics. https://www.iii.org/

[4] Policygenius. (2025). “Term Life Insurance Rates by Age and Coverage Amount.” Life Insurance Pricing Data. https://www.policygenius.com/

[5] National Association of Insurance Commissioners. (2024). “Whole Life Insurance Costs and Returns Analysis.” NAIC Consumer Guide. https://content.naic.org/

Educational Disclaimer

This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute insurance advice, financial planning recommendations, or personalized guidance. Insurance needs vary significantly based on individual circumstances, state regulations, and specific risk profiles.

Before purchasing, modifying, or canceling insurance coverage, consult with licensed insurance professionals and financial advisors who can evaluate your specific situation. Policy terms, coverage limits, exclusions, and pricing vary substantially among insurers and change over time.

The calculations, examples, and recommendations presented represent general educational frameworks, not personalized advice for your situation. Always read policy documents carefully, understand coverage limitations and exclusions, and verify that coverage matches your actual needs before purchasing.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is a financial educator and the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven platform dedicated to explaining the mathematics behind wealth building, investing, and risk management. With expertise in financial analysis and evidence-based money management, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable guidance.

His work focuses on helping individuals understand the cause-and-effect relationships that drive financial outcomes, enabling informed decisions based on data rather than marketing or emotion. Max emphasizes conservative, mathematically sound approaches to insurance, investing, and wealth building.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides comprehensive financial education covering insurance fundamentals, investment principles, budgeting strategies, and the analytical frameworks that support long-term financial success.